Fragmentary Notes on a Few Pertinent Questions of Marxist Political Economy in the Special Context of Certain Ongoing Debate

Abhinav

Communists seek truth from facts, not the other way round. In other words, theory is the scientific generalization of the experience of practice. Of course, in its turn, scientific theory leads practice, takes it to the higher level and in the same process develops itself. Therefore, besides mastering Marxist theory, we communists study the concrete facts and experience of social practice. It is only through scientific theory that one can reach the level of essence, by penetrating the appearance and it is only through social practice that theory develops. In the dialectical development of the movement of the working class, sometimes the aspect of theoretical struggles dominates, and at others the aspect of social practice becomes dominant, though neither of two is non-existent at any moment.

Before we move forward, some important points need to be emphasized.

Against Certain Common Sense Notions Ascribed to Marx and Marxism

The general anti-establishment notions about capitalism often do more harm than benefit. Some of the common-sense notions incorrectly ascribed to Marx and Marxism in general are childish. For example, the theory of absolute impoverishment of the working class, the theory of unregulated “maximum profits” by monopoly capital, the merger or fusion of certain corporations and the bourgeois state, theory of under-consumptionism, etc. Most of these notions characterize the thinking of populists and petty-bourgeois romanticists, the ones you can easily find in the protests like OWS, among the Democratic Socialists of the US, revisionists, reformists, and the likes.

Such incorrect notions imposed upon Marx are particularly harmful because they make Marx and Marxism prone to “easy refutation”. For example, it can be shown with factual evidence that the theory of absolute impoverishment of the working class cannot be sustained. One of the major bourgeois vulgar neoclassical economists Paul Samuelson, in fact, does precisely the same. First he proves that the notion of absolute impoverishment of the working class cannot be sustained empirically and therefore Marx was wrong! That is the reason why such incorrect notions ascribed to Marx and Marxism are very harmful and some bourgeois economists intentionally impute such incorrect notions to Marx. Similarly, the theory of “maximum profits” as distinct from Marx’s concept of surplus-profit is unscientific as well as absurd and does not hold in the face of concrete evidence.

It is essential to defend Marx against such layman’s notions in order to save the revolutionary scientific core of Marxism as the science of revolution.

The Theory of “Absolute Impoverishment of the Working Class” And Marx’s Theory of Value of Labour-Power, Wages and Relative Surplus-Value

As we mentioned above, one such layman’s notion is that of the absolute impoverishment of the working class. Let us dwell on this for a moment. This notion argues that working class becomes increasingly poorer and more pauperized with the development of capitalism and especially in the stage of monopoly capitalism. Marxism does not hold any such notion. Marx’s theory is of relative impoverishment of the working class. This simply means the relatively declining share of wages in the newly produced value vis-à-vis profits. This happens due to the historical decline in the value of labour-power owing to the increasing productivity of labour in the branches that produce basic wage-goods. It is very much possible that the profits as well as wages, both increase absolutely, even when wages are declining relatively as a share of newly-produced value. Marx very clearly explained that it is the historical tendency of capitalism to decrease the value of all commodities, including labour-power, in the chapter on relative surplus-value in the first volume of ‘Capital’. Those who do not understand that the value of labour-power historically declines under capitalism do not understand Marx’s theory of relative surplus-value.

The decline in the value of labour-power does not necessarily mean decline in the real wages, though the capitalist class also depresses real wages of the working class, especially, when it is not already at the level of physical minimum and the organization of the working class cannot prevent it from doing so. The capitalist class also depresses the wages below the value of the labour-power, especially in times of crises, though it cannot be a long-term sustainable situation. Therefore, in certain periods, we witness the absolute impoverishment of the working class as well. However, that situation is also reversed at times due to a variety of factors. For instance, in periods of boom, due to increased demand of labour, the average wages also go up. The same can happen due to a strong and organized working class movement, given the limits posed by the accumulation of capital allow.

Then what are the factors that determine the movement of wages? The movement of wages is determined historically by the lower limits fixed by the bare minimum requirements of the workers (which themselves vary due to the ‘historical-moral’ element involved in the determination of the value of labour-power though it cannot be pushed below the level of physiological minimum needs for a protracted period of time, as Marx pointed out) and the higher limits posed by accumulation of capital. In other words, wages cannot fall below the value of labour-power for a protracted period of time so that the working class is not able to reproduce itself physically or is able to reproduce itself only in a crippled state; secondly, the wages cannot rise above the value of the labour-power so much so that the accumulation of capital becomes impossible. Marx explains in the first volume of ‘Capital’:

The ultimate or minimum limit of the value of labour-power is formed by the value of the commodities which have to be supplied every day to the bearer of labour-power, the man, so that he can renew his life-process. That is to say, the limit is formed by the value of the physically indispensable means of subsistence. If the price of labour-power falls to this minimum, it falls below its value, since under such circumstances it can be maintained and developed only in a crippled state, and the value of every commodity is determined by the labour-time required to provide it in its normal quality. (Marx, Capital, Vol-1)

Marx also writes:

On the other hand, the number and extent of his so-called necessary wants, as also the modes of satisfying them, are themselves the product of historical development, and depend therefore to a great extent on the degree of civilisation of a country, more particularly on the conditions under which, and consequently on the habits and degree of comfort in which, the class of free labourers has been formed. In contradistinction therefore to the case of other commodities, there enters into the determination of the value of labour-power a historical and moral element. Nevertheless, in a given country, at a given period, the average quantity of the means of subsistence necessary for the labourer is practically known. (ibid)

Marx explains further:

It is these absolute movements of the accumulation of capital which are reflected as relative movements of the mass of exploitable labour power, and therefore seem produced by the latter’s own independent movement. To put it mathematically: the rate of accumulation is the independent, not the dependent, variable; the rate of wages, the dependent, not the independent, variable. (ibid)

Finally, Marx shows how movement of wages is determined:

The correlation between accumulation of capital and rate of wages is nothing else than the correlation between the unpaid labour transformed into capital, and the additional paid labour necessary for the setting in motion of this additional capital. It is therefore in no way a relation between two magnitudes, independent one of the other: on the one hand, the magnitude of the capital; on the other, the number of the labouring population; it is rather, at bottom, only the relation between the unpaid and the paid labour of the same labouring population. If the quantity of unpaid labour supplied by the working class, and accumulated by the capitalist class, increases so rapidly that its conversion into capital requires an extraordinary addition of paid labour, then wages rise, and, all other circumstances remaining equal, the unpaid labour diminishes in proportion. But as soon as this diminution touches the point at which the surplus labour that nourishes capital is no longer supplied in normal quantity, a reaction sets in: a smaller part of revenue is capitalised, accumulation lags, and the movement of rise in wages receives a check. The rise of wages therefore is confined within limits that not only leave intact the foundations of the capitalistic system, but also secure its reproduction on a progressive scale. The law of capitalistic accumulation, metamorphosed by economists into pretended law of Nature, in reality merely states that the very nature of accumulation excludes every diminution in the degree of exploitation of labour, and every rise in the price of labour, which could seriously imperil the continual reproduction, on an ever-enlarging scale, of the capitalistic relation. (ibid)

Thus, within these limits, namely, the physiological minimum and the limits posed by accumulation of capital, the wages move due to many factors. The most important one is the class struggle of the working class to increase its share in the newly-produced value, namely, wages. The other is the overall condition of the capitalist accumulation, in other words, whether the capitalist economy is in the phase of prosperity, stagnation or crisis. The supply and demand of labour is only a function of the industrial cycle, or the movements of accumulation, and not an independent variable as such. Under the combined impact of these factors, the wages move within the above limits.

This also means that the value of labour-power and the real wages can move in different directions in capitalist mode of production. Those who do not understand this, actually confuse the value of labour-power with real wages. The first is the magnitude of socially-necessary labour required to produce the means of subsistence of the workers; the second refers to the basket of consumer goods that a worker can buy with his money wages. However, it is essential to remember that wages, as a historical tendency, fluctuate around the value of labour-power just like the prices of all commodities hover around the centre of gravity of their value. Marx explains succinctly in the first volume of ‘Capital’ how the value of labour-power and real wages can move in different directions under capitalist mode of production:

The value of labour-power is determined by the value of a certain quantity of means of subsistence. It is the value and not the mass of these means of subsistence that varies with the productivity of labour. It is however possible that owing to an increase in the productivity of labour both the worker and the capitalist may simultaneously be able to appropriate a greater quantity of means of subsistence, without any change in the price of labour-power or in surplus-value. Let the value of labour-power be 3 shillings, and let the necessary labour-time amount to 6 hours. Let the surplus-value be, similarly, 3 shillings, and the surplus labour 6 hours. Now, if the productivity of labour were to be doubled without any alteration in the ratio between necessary labour and surplus labour, there would be no change in the magnitude either of the surplus-value or of the price of labour-power. The only result would be that each of these would represent twice as many use-values as before, and that each use-value would be twice as cheap as it was before. Although labour-power would be unchanged in price, it would have risen above its value. However, now assume a fall in the price of labour-power, not as far as Is. 6d., the lowest possible point consistent with its new value, but to 2s. 10d. or 2s. 6d. This lower price would still represent an increased quantity of means of subsistence. In this way it is possible, given increasing productivity of labour, for the price of labour-power to fall constantly and for this fall to be accompanied by a constant growth in the mass of the worker’s means of subsistence. But in relative terms, i.e. in comparison with surplus-value, the value of labour-power would keep falling, and thus the abyss between the life-situation of the worker and that of the capitalist would keep widening. (ibid)

The historical tendency of capitalism is to reduce the value of the labour-power because productivity increases in all branches of production including the ones producing wage-goods. This leads to decline in the per unit cost as well as the price of these wage-goods. The reason is that the increase in the productivity of labour means that the same or even less amount of value will be distributed over a larger mass of use-values. This happens with all commodities in capitalism including the commodities that enter into workers’ consumption. Therefore, an important thing to remember is that capitalism decreases the value and therefore relative prices of all commodities, including wage-goods and therefore, that of labour-power.

Misconceptions Regarding the Origin of Profit

Again, let us see how common sense reasoning functions. Many people doubt this historical tendency of capitalism, because they believe that the origin of profits is high prices (conjured up by speculation, intrigues, and conspiracies of monopolies!). Capitalist class does not increase its profits by continuously increasing prices, though price increase may take place due to a variety of factors in the short-run, including speculations in the conditions of sudden volatility in prices due to under-supply, etc.

Capitalist class increases its profit precisely by the methods which objectively decrease the value of labour-power. Why? Because as capitalism develops, it becomes increasingly difficult for the capitalist class to increase the length of the working-day continuously and thus absolutely increase the surplus-value. This happens because of two reasons: one, there is a physical limit to increasing the length of the working-day; and second, the working class resists any such move of the capitalist class. Therefore, the capitalists increase the rate of surplus-value without increasing the length of the working-day, but by increasing the relative portion of surplus labour-time and decreasing the portion of necessary labour-time in the working-day. This can happen only when productivity increases in the sectors that produce the wage-goods.

The capitalists in all sectors are obliged to increase the productivity of labour, because competition in the market to sell the cheapest compels them to decrease their cost of production and this is done by introducing new methods of production and thus increasing the productivity of labour. However, the rise in productivity of labour in industries other than the ones that produce wage-goods, does not lead to decline in the value of labour-power. They result in cheapening of the commodities because the same value is distributed over a larger mass of use-values. However, this same process of competition also compels the capitals active in the wage-goods sector to introduce new methods of production, increase the productivity of labour and thus decrease the value of their commodities. As a result, the value of labour-power also decreases historically. This, of course, does not necessarily mean a decline in the real wages, as we pointed out earlier.

When the value of labour-power decreases, the capitalist class also attempts to depress the wages of the working class, so that the benefits of increase in the productivity of labour do not accrue to the working class but to the capitalist class, as Marx so clearly showed in ‘Capital’. As a result, if one looks at the historical movement of real wages, they will find that these have been hovering around the historical movement of the value of labour-power in all countries.

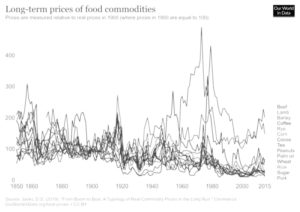

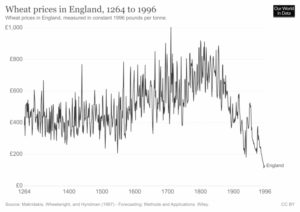

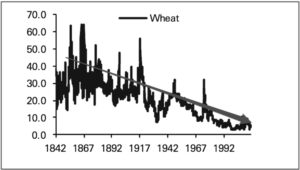

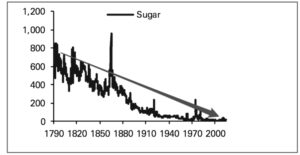

Historical Prices of Food in Capitalism and the Question of Monopoly-prices

It can be proven with empirical data that food prices have historically been declining. Refer to the figures attached with this essay to see that the relative prices of all basic food items have been decreasing since the beginning of capitalism, as well as, since the beginning of the phase of monopoly capital. Just an example: if we take 1900 as the base year and 100 as the base number, then in 1950, the price of corn was 134.8 and in 2000 it was 23.4. For rice, in 1950 the index fell to 62.70 from 100 in 1900; in 2000, it fell further to 15.08. For wheat, it rose from 100 in 1900 to 106.4 in 1950 but fell to 17.23 in 2000. (https://ourworldindata.org/food-prices). The Deutsch Bank data confirms this result (https://www.businessinsider.in/finance/these-charts-show-just-how-incredibly-cheap-food-is-these-days/articleshow/48871445.cms)

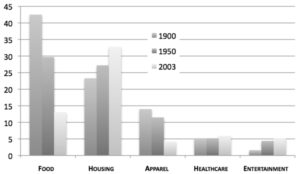

Also, see that the portion of wages spent on food items has been steadily declining as a historical tendency. According to USDA data, the share of income spent on food in 1982 in the US was 8.3 percent; by 2011, it fell to 5.7 percent (https://www.aei.org/carpe-diem/think-food-is-more-expensive-today-than-in-the-past-its-not-its-now-cheaper-than-ever-before/).

We are talking about a country with highest levels of monopolization in all the industries including wage-goods industries and agriculture. This also proves Marx’s point that wages are also determined by what he calls ‘historical-moral element’ since the very definition of bare minimum requirement is changing with the general level of civilization and particularly the class consciousness and organization of the working class. Even in the worst period for the American working class (from 1970s to present), its expenditure on food has decreased, even though its real wages have remained stagnant. The increasing share of income spent on many other commodities and services shows that the very definition of the ‘bare minimum requirements’ now includes these as inherent part of these minimum needs.

See the above images to comprehend the trend of prices of some basic food items in some of the major capitalist countries. One of the images (figure 5) shows the historical real prices of wheat in England since the Thirteenth century. This is particularly interesting as it shows a secular decline in the prices of wheat after the advent of capitalist mode of production.

Of course, the decline in prices of food is a long-term tendency and with data of a smaller time period, it can be shown that food prices have risen! For instance, a one decade or two decade data, especially from periods of crises when real wages decline or from the small periods of speculative frenzy in prices of commodities, would certainly show an increase in the prices of food items. However, the secular tendency in capitalism is that of declining prices of wage-goods and therefore declining value of labour-power as we can see from the above data and attached graphs. This is precisely the way in which capitalist class appropriates relative surplus-value. Those who negate it and claim that in the phase of monopolies, this law ceases to function because monopolies exact monopoly-rents in wage-goods sector, conspire to increase prices of wage-goods speculatively, etc., are actually failing to understand a general law of capitalism as revealed by Marx and which applies to the entire history of capitalism! Also, they confuse the arena of distribution of surplus-value and therefore profits with the arena of production of surplus-value. Monopoly-prices or short-term speculative rise in prices does not produce surplus-value, but only lead to redistribution of surplus-value among different capitals. Such vulgar philistines who do not understand this exist in our country as well and imagine that in the monopoly stage of capitalism, the general laws of capitalism cease to function and now profits are outcome of intrigues and conspiracies of the monopolies! One example of such philistines is ‘The Truth’/’Yathaarth’ bunch of idiots who are constantly spreading ignorance and non-sense about Marxism. See what Marx says about such dimwits:

The capitalist’s real profit is largely profit upon expropriation and the “individual labour” of the capitalist has an especially wide scope in this field, where it is not a question of the creation of surplus-value but of the distribution of the aggregate profit of the whole class of capitalists among the individual members in the field of commerce. This does not concern us here. Certain kinds of profit, those based on speculation for example, are restricted merely to this field. It is therefore quite impossible to examine them here. It is an indication of the bovine stupidity of vulgar economy that (particularly in order to represent profit as “wages”) it confuses this with profit insofar as it originates in surplus-value. (Marx, Theories of Surplus Value, Vol 3)

Some people argue that monopoly capital exacts monopoly-rents through monopoly-prices in the wage-goods sector. This argument is incorrect. If we study the historical food prices in the countries which have been the trailblazers in monopolization in the branches of production that produce wage-goods, especially, food, we see that they have steadily declined as a secular tendency. We saw some representative data above. The reason is simple: if a company establishes its monopoly in a sector that produces a basic wage-good like food, it cannot impose monopoly-prices because it hurts the entire capitalist class, including other monopolists; secondly, the companies that establish monopoly in wage-goods sector too, are investing not only in wage-goods industry but also in other branches of production. If the prices of wage-goods are increased by a monopoly-price, they too will lose; third, if a big capitalist with monopoly in a branch of production that produces wage-goods, does try something of that sort, the rest of the capitalist class, including monopolists will rally against it, oblige the capitalist state to act against it, as capitalist state cannot and does not identify itself with one or a few monopolists. It represents the long-term collective class interests of the capitalist class in general. Of course, at one time one faction might be dominant; at others some other faction might be dominant in the state power. However, that does not mean that the state becomes a broker of one faction and disregards the long-term collective class interests of the capitalist class. Needless to say, capitalist class does not here mean different echelons of petty-bourgeoisie.

Historical Movements of Wages in Advanced Capitalist Countries and Relatively-Backward Capitalist Countries since the 1970s

It is true that the real wages that had been increasing in the advanced capitalist countries till the 1970s, became stagnant. The real wages in advanced capitalist world have either stagnated or declined since the crisis of 1973. The reason is simple: before this crisis, in the so-called ‘golden era’ of capitalism, the real wages of the working class in the advanced capitalist world were generally way above the value of labour-power. One factor was also the colonial loot and plunder by imperialist countries, with which they had been able to bribe a section of workers in these countries, as Engels and Lenin had pointed out. As this mode of direct colonial loot and plunder receded, new ‘regimes of accumulation’ and ‘modes of regulation’ were bound to emerge, if we borrow from the terminology of Regulation School. It obviously does not mean that mode of surplus extraction changed or some new mode of exploitation of labour emerged. It simply means that the particular relations between labour and capital that characterized the period of Keynesianism and welfarism in the advanced capitalist countries were replaced with a set of new relations, that led to informalization and casualization of the working class and deregulation of labour markets, not to mention deregulation of financial markets leading to financialization in an unprecedented way. This also required a change in the role of state and it was this changed role that informed the new ‘modes of regulation’. Deregulation and informalization do not mean absence of regulation, but a change in the form of regulation.

Anyway, the crisis of the 1970s led to the emergence of these new ‘regimes of accumulation’ and ‘modes of regulation’ known as ‘neoliberalism’. Thatcherism and Reagonomics were nothing but political articulations of the policies of neoliberalism. Decolonization had been progressing in this period. The direct colonial loot and plunder of the colonies and semi-colonies was becoming a thing of the past. These changes coupled with the crisis of profitability and collapse of Keynesian welfare economics led to the emergence of the policies of neoliberal globalization.

It is this period in which the real wages of working class in advanced capitalist countries too has stagnated or even declined, which means, many of privileges enjoyed by certain sections of the working class in these countries are being slowly snatched away. Also, in most of these countries, an immigrant informal working class has emerged which is in extremely vulnerable conditions.

In the so-called developing capitalist world, which has become the new centre of manufacturing in the last 30 years, the number of workers has increased phenomenally. Their wages have been kept at the physical minimum and the working class has largely been unable to fight to increase its share in the newly-produced value, except a few exceptions. The reason is that this entire period coincides with what has now been called ‘the Long Depression’. The real wages have remained mostly stagnant. The real wages grew at only 3.7 percent per annum between 1993-94 and 2011-12 in India. If we compare it with the rate of profit, we find that the working class has become relatively more impoverished, or the share of wages has been steadily declining in total newly-produced value.

Secondly, most of the increase in real wages is relevant only for the upper echelons of the working class, whereas the real wages of the informal sector working class has either remained stagnant or has even declined in some cases in this period. Between 2006 and 2017, according to the Global Wage Report of ILO, the real wages in India increased faster than other South Asian countries like Bangladesh, Pakistan and Nepal. However, it grew at a slower pace than China, Vietnam, Thailand, etc. In the last 2 years, that is, during the period of Covid-19 and lockdown, the real wages of the informal workers declined drastically by around 22.6 percent. We know that it is an exceptional period and this was bound to happen in conditions that have been prevailing for last one and a half years. In countries, where lockdowns have ended and some sort of recovery has started, a rebound has begun, though it is too early to make firm judgements about their future trajectories (see Michael Roberts’ blog ‘The Next Recession’ for data).

Therefore, the condition of working class in the so-called ‘Third World’ has deteriorated and their real wages have remained stagnant for the majority of workers, in the period of ‘Long Depression’. This is precisely what Marx had predicted: the movement of wages is dependent on the industrial cycle; in other words, it depends on the state of profitability. If the capitalist system is in stagnation or crises, the wages generally decline to the physical minimum and sometimes below the value of labour-power for certain periods of time.

However, it is essential to understand that this does not happen due to monopolies exacting monopoly-rents in the wage-goods sector. Such an explanation is not an explanation at all. The crisis of profitability and resultant unemployment and decline in average wages is the real reason. Claiming that the conditions of the working class deteriorated because monopoly capitalism exacts monopoly-rents on wage-goods and thus makes the working class absolutely impoverished has nothing to do with Marx’s arguments and such claims cannot be sustained factually.

Thus, the claim that monopolies will increase prices of food through monopoly-prices or speculative prices is a claim that falls flat in front of concrete evidence from the long-term history of capitalism. Please refer to the above figures to see data. Speculative increases in prices of wage-goods regularly takes place and it is a short-term phenomenon as we shall see. Moreover, speculative manipulations with the prices of food in these short periods are not something limited to monopoly capitalists. For instance, at present, the kulaks and farmers producing oil-seeds are making good of price-volatility due to under-supply of edible oils by selling oilseeds at exorbitantly high speculative prices, which are more than double of declared MSP! However, the flunkeys of kulaks in the left movement do not even mention the role of rich farmers and kulaks in this speculation! That would be kufr for them!

The Relationship Between Capital and Simple Commodity Producers and the Relation Among Capitalists

Some people also do not make a distinction between how capitalist class, including monopolists, plunders the simple commodity producers and the way in which commercial capitalists (including monopolies) appropriate a portion of the surplus-value of the entrepreneur capitalists (including monopolists) as commercial profit.

Now, let us move to this particular confusion that pervades the ranks of left circles.

We know that even in countries with fairly advanced capitalist relations, various forms of simple commodity production continue to exist alongside the advanced capitalist commodity production. Small and marginal peasants, who have in principal become semi-proletariat, are also simple commodity producers, because they are also involved in commodity production though they do not exploit wage-labour. How do capitalists, including monopolies, plunder simple commodity producers in capitalist countries? It is the same way in which capital in general plunders the simple commodity producers. It is by forcing the simple commodity producers to undersell their products to the capitalist. The capitalist appropriates not only a part of surplus-labour of the simple commodity producers, but, in most of the cases, the entire surplus-labour, and often a part of the necessary-labour of the simple commodity producers as well (the “wages” that he pays to himself, as Marx called it). It does so by forcing the simple commodity producers to sell their commodities much below their value to the capitalist. This is not something that is done only by monopoly capital, but capital in general. Even some textbooks of political economy published by great parties like the Soviet Party are not accurate on this point, the reason of which will be discussed later. The entire onus of plundering of simple commodity producers through unequal exchange is often put on the monopoly capital alone, whereas, Marx showed very clearly in ‘Capital’ that the ruin of the simple commodity producers through unequal exchange is one of the general properties of capital, though in colonies, semi-colonies and neo-colonies this was done mainly by imperialist capital, which is obvious. This is a very important aspect of Marx’s political economy which reveals the way in which capital becomes a dominant social power by taking over commodity production and subsuming labour.

This is something that is done in agriculture as well. In fact, the rich farmers and kulaks have been precisely doing this with the small and marginal peasants of India, who are not capitalist producers but simple commodity producers, because they do not exploit wage-labour. The second way in which capital plunders the simple commodity producers is through loans that the latter require not only for production but also for other needs. This too is already being done by the rich farmers and kulaks in India. Read the following news:

This news simply confirms a fact that had been known to all common village folk in India for a long time and fact perfectly understood and causally-explained by Marx one and a half century ago! In fact, if you look at the data of depeasantization, you will find that one of the most important reasons for poor and marginal peasants “leaving agriculture” is the debt-trap of large farmers and underselling of their produce to the large farmers. The last two decades have seen almost 20 million small and marginal peasants “leave agriculture”, or in Marxist terms, being proletarianized.

Will the monopolies do the same to the simple commodity producers? Yes, though in a different way. Monopolies will certainly continue the process of forcing simple commodity producers to undersell their products to them and thus proletarianization will continue as before. Currently, it is being done by the rich farmers and kulaks under informal contract farming. In the future, it will be done by the big companies as well. What is the difference here? The principal exploiter of the simple commodity producers will be changed from rich kulaks and farmers to big companies or at least both will become co-sharers in this loot and feast on the plunder of small commodity producers.

The simple commodity producers of Indian agriculture are also semi-proletariat as more than 70-80 percent of their income comes from wage-labour, not cultivation. The small and marginal peasants will have to fight against the big companies as their hegemony is established, not only for higher wages in their capacity as agricultural workers, but also against this plunder through unequal exchange in their capacity as simple commodity producers. The latter struggle is a lost cause, as Marx, Engels and Lenin have taught us. Vis-à-vis this second struggle, the task of communists is to help them in their immediate struggle and educate them that this problem cannot be solved as long as capitalist mode of production exists. There is no future of small-holding and simple commodity production in capitalism.

However, this much is certain: there is no reason whatsoever for the agricultural workers, poor and marginal peasants to fight for maintaining the hegemony of their current exploiters and oppressors, namely the rich farmers and kulaks. In most likelihood, the rich farmers and kulaks too will not be wiped out from the agricultural scene as this has not happened in any of the major capitalist country where monopolies have long entered the sector of agricultural production. A part of them will diversify their capital investment, move to some other sectors, and another part will be co-opted by the big agro-companies into their supply-chains, as the experience from around the world confirms. As a consequence, both of them will continue to exploit and oppress the rural poor and would constitute enemy classes.

We also need to make a clear distinction between the relation between the big capitalist firms and simple commodity producers on the one hand (which is based on unequal exchange as we saw above) and the relation between the big capitalist firms and capitalist farmers on the other. The example of the US and Europe shows that the rich farmers do exist as a class in these countries. Many of these rich farmers are involved in contract farming with big companies. What is the relation between the big companies and these rich farmers? It is certainly not like the relation between capital and simple commodity producers.

In this case, the big capitalist farmers appropriate the surplus-value by exploiting the wage-labour involved in production. They sell the product to these companies at their value, if the companies are buying these agricultural products as raw materials for their industrial production of other commodities. If the companies in question are simply commercial capitalists involved in selling the agricultural product, then the surplus-value is divided into the commercial profit and what Marx called ‘profit of the enterprise’. Wherever big companies enter directly into production, they obviously compete against the rich farmers and in most likelihood become a cause of the ruin of at least a section of rich capitalist farmers as well. However, that is a simple case: the competition between big capital and comparatively smaller capital.

The proletariat does not and should not carry the responsibility to save the smaller capitalists from the bigger capitalists, both of whom are its exploiters. The proletariat along with lower and lower-middle peasantry, would organize and prepare to fight for the independent class interests of its own and these ally classes. For these ally classes, proletariat can also make immediate sacrifice of some of its interests as well or can put them aside for the time being. However, these ally classes do not, of course, include rich kulaks and capitalist farmers, the exploiters of wage-labour, plunderers of poor peasants and oppressor of dalit working masses.

Some people also confuse the underselling of agricultural produce by small and marginal peasants, that is, simple commodity producers, to capitalists, including the monopoly capitalists, with monopoly-price and monopoly-rent. However, these two are two totally different forms in which profit is made by the capitalists. The first does not lead to a monopoly-price and therefore increase in market prices. The second leads to formation of a monopoly-price and therefore increase in market-prices.

It is true that even when capitalists, including monopoly capitalists, buy agricultural products of simple commodity producers, like small and marginal peasants, they do not sell it cheaper to working masses. Why would they?! Therefore, on the basis of unequal exchange with the simple commodity producers, they earn extra profits without selling the product cheaper to consumers. However, this too is not monopoly-price or monopoly-rent.

Marx’s View of Speculative Manipulations of Prices of Commodities by the Capitalist Class – I

They can certainly oversell by speculatively increasing prices in certain conditions in which sudden price volatility due to a variety of contingent factors may enter the picture. However, such speculative rise in prices too are not monopoly-rents and they are always temporary because it is precisely this increase in prices due to speculation that eventually leads to decline in effective demand, and/or, if the consumption is not dependent on imports, then a resultant expansion of production and therefore supply, and ultimately a decline in prices. For instance, that is the reason why the Indian capitalist class is more interested in increasing the domestic production of edible oils in order to control such speculative rise in prices of a wage-good, than depending on the international prices and waiting for them to decline. Decreasing the import duties can ease the pressure immediately, but the long-term solution is giving incentive to production of oil-seeds within the country. That is why the government has begun to distribute high-quality oilseeds to capitalist farmers for free, in order to incentivize the production of oil-seeds. Also, that is the reason why the government has agreed to postpone the reduction in import-duties on edible oils (which it has decreased considerably in the past few years) till the beginning of kharif season so that the capitalist farmers have incentive to increase production of oil-seeds. It is noteworthy that these capitalist farmers are already selling oil-seeds at high speculative prices, almost double of declared MSP, in the open markets! There is nothing surprising in that! They are behaving as the profiteers that they are.

In nutshell, historical evidence proves that temporary speculative increase in prices by all capitalists including monopolists notwithstanding, monopoly companies in wage-goods sector seldom impose monopoly-prices and it has never been a protracted phenomenon. The reason is that any such move is resisted by the rest of the capitalist class, including other monopolists. Moreover, making wage-goods dearer is not good for the monopolists in the agricultural sector as well, because upward pressure on wages will eventually cause a decline in their profits too.

Further.

Marx’s Political Economy and Certain Problems of Popular Textbooks of Political Economy

I cannot overemphasize the fact that it is essential to read Marx himself to develop a nuanced understanding of the above questions. However, there has long been a reluctance on part of serious students of Marxism as well as political activists to read Marx’s major works on political economy, most importantly, ‘A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy’, ‘Grundrisse’, three volumes of ‘Capital’ and the three volumes of ‘Theories of Surplus Value’, that is, the fourth volume of ‘Capital’. It is heartening to see that certain publications have started to publish unedited economic manuscripts of Marx, which, I believe, would possibly reveal new dimensions of Marx’s approach and method in political economy. Anyway, as a result of this reluctance, partly stemming from the thrall in which Marx is held (rightly so!), there has been a tendency to rely too much on the popular textbooks of political economy published by great parties like the Soviet party, the Chinese party as well as the British party.

There is no harm in relying on these textbooks for basics of Marxist political economy. For instance, for the likes of the giddyheads gathered around ‘The Truth’/’Yathaarth’ magazine, who do not even understand the very basic concepts like value, price, prices of production, even fail to distinguish between use-value and exchange-value and make claims such as that the value of labour-power was estimated in the Soviet socialist transition and labour-power is a commodity in socialism, etc., these textbooks would be quite helpful, as they do not make any glaring mistake on these questions. Though, I doubt that philistines like Ajay Sinha and Mukesh Aseem would be able to understand even these textbooks as they have hitherto demonstrated a remarkable ability to misunderstand the simplest of things!

However, one also needs to understand that as we approach the more contemporary and complex questions like monopoly capital, imperialism, certain aspects of socialist transition, we must read these textbooks with a pinch of salt. One also has to understand the historical context in which some of the most popular and important textbooks of political economy were prepared. It was the period between 1930s and 1950s, in the case of the British and Soviet textbooks and 1960s and 1970s in the case of Chinese textbooks. This period was characterized by an undue over-optimism regarding the collapse of monopoly capitalism, its decadence and moribund character during and after the Second World War, playing a particularly important role in such over-optimism. The impact of mechanical thinking can be discerned in the writing of these textbooks.

For understanding the basic concepts like social value, prices of production, market-price, some questions pertaining to the socialist transition, ground-rent, etc., these textbooks are broadly correct and helpful and for people like ‘The Truth’/’Yathaarth’, they are certainly essential as we mentioned above, because these folks do not even understand the foundational concepts of Marxist political economy like what is labour-power, what is value, what is price, what are prices of production, what is monopoly-price and monopoly-rent, what is ground-rent, etc.

However, on few accounts, there are some problems in these textbooks. For instance, most of these textbooks present a multi-causal explanation of capitalist crises. While few of them certainly put the law of tendential fall in the rate of profit (LTFRP) at the centre, they fall short of explaining how it is this secular tendency of the rate of profit to fall that is the underlying fundamental cause of crisis leading to the phenomenal manifestations such as over-production, over-accumulation, disproportionality, under-consumption, as well as over-financialization. A more elaborate explanation would have been better.

In some other textbook, the mention of law of tendential fall in the rate of profit is made, but over-production thesis dominates. However, a multi-causal explanation is eclecticism and the failure to identify the fundamental contradiction and principal contradiction. In other words, it fails to comprehend the monist nature of science. Marx’s theory of crises is mono-causal. Guglielmo Carchedi is on point when he says,

some Marxist authors reject what they see as “mono-causal” explanations, especially that of the tendential fall in the rate of profit. Instead, they argue, there is no single explanation valid for all crises, except that they are all a “property” of capitalism and that crises manifest in different forms in different periods and contexts. However, if this elusive and mysterious ‘property’ becomes manifest as different causes of different crises, while itself remaining unknowable, if we do not know where all these different causes come from, then we have no crisis theory…if crises are recurrent and if they have all different causes, these different causes can explain the different crises, but not their recurrence. If they are recurrent, they must have a common cause that manifests itself recurrently as different causes of different crises. There is no way around the “monocausality” of crises.

One cannot agree more.

Second question on which a clear-cut error can be found in some of these textbooks is their emphasis on some kind of imminent collapse of capitalism in the phase of monopoly capitalism, as if, revolution was round the corner. History has proven that this optimism was misplaced. Though, today we can understand the historical context in which this false optimism originated, yet, we should have no qualms in accepting that this assessment has been proven wrong by history and certainly was not correct even when it was made.

Third issue on which some of these textbooks are incorrect is their theory of absolute impoverishment of the working class in the age of monopoly capitalism. Generally, these textbooks present data of fall in the real wages, sometimes below the value of labour-power, from 1910s to 1930s. Towards the end of the 1920s and beginning of the 1930s, the real wages drastically fell. This is taken as an evidence of absolute impoverishment or degradation of the working class in the age of monopoly capitalism and it is then presented as a general argument applicable to the entire stage of monopoly capitalism, that is, imperialism. Empirical evidence from last eight decades do not support such argument. The treatment of empirical data in these textbooks too is too fragmentary and limited to make such a claim because the period is one of Great Depression and a drastic fall in wages and absolute impoverishment can be expected. Such a small time-bracket does not represent a secular tendency of capitalism. The same theory will fail to explain considerable increase in the real wages in the so-called ‘golden era’, till the mid-1970s. Needless to say, that era was still the era of monopoly capitalism!

The Chinese textbook (The Shanghai Textbook) too has serious inaccuracies on many points including crisis theory as well as monopoly capital. Some CPC party writings had propounded a theory of ‘era of final collapse of imperialism’ that was certainly incorrect and this theory had profound impact on party textbooks and writings in general.

Here too, the historical context in which these textbooks were written plays a pivotal role. The extreme moribund and decadent character of imperialism was to be emphasized, and correctly so. However, these textbooks overdid it and in the process supported a theory which Marx had abandoned and criticized since the 1850s, namely, the theory of absolute impoverishment of the working class. In its zeal to prove this theory, for instance, the Soviet textbook emphasized that the reason for this absolute impoverishment of the working class was that the monopolies will exact monopoly-prices on wage-goods as well and this will lead to absolute impoverishment of the working class. In theoretical exposition of things, one has to keep away from the temptation of agitating the masses! Here the task, in the words of Gramsci, is to be a ‘pessimist’ (bereft of irrational passion) and focus on the scientific accuracy of theoretical generalizations. The agitational articulations of correct theorizations are the next step where one has to deal with the complex dialectics of popularization and accuracy. However, one stage cannot be mixed up with the other.

Some people agitate themselves in the most romantic fashion, while analyzing something. As a result, they end up with disastrous results. The same is true for Ajay Sinha, “general secretary” as well! In one of his pamphlets on the West Bengal Assembly elections, our Don Quixote de la Patna claimed that “corporates are fighting elections!” But then, against whom? All bourgeois parties as well as the bourgeois state itself, are mere stooges of corporate capitalist class, according to Ajay Sinha; then against whom was the corporate capital contesting the elections? Such are the ridiculously and ludicrously inane results of “analysis” when the analyst indulges in romantic self-agitation!

The General Law of Prices of Wage-Goods Under Capitalism (including Monopoly Capitalism)

Anyway, we have seen with concrete data that the history of prices of wage-goods and most important wage-goods (food) proves this theory as presented in these textbooks as incorrect. In countries with the highest degree of monopolization in agriculture, the prices of foods have been declining steadily for past 100 years. If we believe that monopolies are exacting monopoly-rents through monopoly-prices in food, then by now, the real wages of the working class should have gone so much below the value of the labour-power, that the workers should not have been able to reproduce themselves even in the most emaciated form!

Lenin and Marx were very clear about it: in the sectors that produce the necessaries of life that go into the consumption of workers, monopoly-pricing, monopoly-rent, absolute ground-rent, in short, anything that causes increase in real relative prices, are detrimental to accumulation of capital in general and therefore to the long-term collective class interests of the capitalist class itself and that is why they cannot be a sustainable situation in industries that produce wage-goods. Marx points out:

If the commodity with the monopoly price is part of the workers’ necessary consumption, it increases wages and thereby reduces surplus-value, as long as the workers continue to receive the value of their labour-power. It could press wages down below the value of labour-power, but only if they previously stood above the physical minimum. In this case, the monopoly price is paid by deduction from real wages (i.e. from the amount of use-values that the worker receives for the same amount of labour) and from the profit of other capitalists. (Marx, Capital, Volume 3, Penguin Edition)

Similarly, Lenin explains the same thing, quoting Kautsky in approval, that applies to Absolute Rent as well as monopoly-rent and monopoly-price:

To proceed: the second distinction between differential rent and absolute rent is that the former is not a constituent part affecting the price of agricultural produce, whereas the latter is. The former arises from the price of production; the latter arises from the excess of market price over price of production. The former arises from the surplus, from the super-profit, that is created by the more productive labour on better soil, or on a better located plot. The latter does not arise from the additional income of certain forms of agricultural labour; it is possible only as a deduction from the available quantity of values for the benefit of the landowner, a deduction from the mass of surplus value—therefore, it implies either a reduction of profits or a deduction from wages. If the price of foodstuffs rises, and wages rise also, the profit on capital diminishes. If the price of foodstuffs rises without an increase in wages, then the workers suffer the loss. Finally, the following may happen— and this may be regarded as the general rule—the loss caused by absolute rent is borne jointly by the workers and the capitalists. (Lenin, Collected Works, Volume 13)

This was true in the period of pre-monopoly capitalism and it is true in the period of monopoly capitalism, as we can see in the figures attached quoted above. Those who claim otherwise do not understand the basic logic and arbitrarily claim that this law must become ineffective for some reason in the stage of monopoly capitalism! Why? There is no reason given by those who argue so. The truth is that the above tendency holds for entire period of capitalism, as long as capital-relation exists, as long as capital exploits wage-labour. The reason is simple: even in the period of monopoly-capitalism, surplus-value is not produced by monopoly-prices or even speculative prices; it is only redistributed by monopoly-prices. Surplus-value is still produced by labour and is still increased at the social aggregate level only by increasing surplus-value and generally by increasing relative surplus-value. That is why the historical decline in the value of labour-power due to historical decline in the prices of food items and other wage goods is totally in congruence with Marx’s teachings.

Marx’s View of Speculative Manipulations of Prices of Commodities by the Capitalist Class – II

Now let us dwell a little bit on the question of speculative rise in prices of wage-goods as well as other commodities, because a lot of nonsense is being thrown by the likes of ‘The Truth’/’Yathaarth’ bunch of imbeciles on the social media. I would be brief and elaborate the basic Marxist position on speculation in points.

First of all, speculation in prices of commodities is something that existed in the pre-monopoly stage of capitalism as well and it has nothing particular to do with the stage of monopoly capitalism. Moreover, it is done by the entire capitalist class, whenever conditions allow, including kulaks, rich capitalist farmers, traders, usurers as well big capitalist class, including monopolies.

Second, speculation and the resultant rise in prices of commodities is always a short-term phenomenon and it cannot last for long, as the particular conditions which trigger speculative manipulations of prices by holding stocks can never exist for a long period of time. That is why Marx writes:

Special filling of the reservoirs—insofar as this is not due to the overstocking of the market, which can happen much more easily in these circumstances than under archaically slow conditions— occurs only for speculative reasons and merely in exceptional cases because of a real or suspected fall or rise of prices…

(The following example demonstrates how closely the keeping of a stock is linked with deficiencies of production…) (Marx, Theories of Surplus-Value, Volume 3)

Third, the particular conditions that give rise to speculative manipulation of prices of commodities are sudden volatility in the prices of commodities due to supply-side shocks or demand-side shocks. In other words, it is the sudden increase in relative demand that creates inflationary pressures on the prices and it is precisely this that leads to speculative manipulations of prices by rich farmers, traders, middlemen as well as big capitalists, including monopolies. Marx explains that hoards of commodities are created only under exceptional conditions, for example, overproduction, where hoards are created due to glut, independent of the will of the capitalists; and due to a bottleneck in circulation, which leads to breaks in supply:

The exclusion of money from circulation would constitute precisely the opposite of its valorization as capital, and the accumulation of commodities in the sense of hoarding them would be sheer foolishness. In fact the accumulation of commodities in great masses is the result either of a bottleneck in circulation or of overproduction. (Marx, Capital, Volume 1)

Marx explains this in the third volume of ‘Capital’ as well, that it is the sudden supply-shocks and resultant price volatility that fuels speculation and further rise in prices:

The supply of an article, however, may fall below its average, as the case with a harvest failure in corn, cotton, etc., while the demand for loan capital grows on the SPECULATION that prices will rise still higher, the most immediate means to make them rise: being to withdraw a part of the supply temporarily from the market. In order to pay for the commodities bought without selling them, gold is obtained by way of commercial “bill of exchange operations”. In this case the demand for loan capital grows, and the rate of interest may rise as a result of this attempt to block the supply of commodities to the market artificially. The higher rate of interest then expresses an artificial reduction in the supply of commodity capital. (Marx, Capital, Vol 3)

We shall later see a few more quotes of Marx, where he explains that it is precisely the under-supply of commodities which lead to speculative manipulations of their prices and it is precisely this speculative increase in prices which eventually becomes a cause of decline of the prices and the end of speculative frenzy.

Had not that been the case, every capitalist in every branch of production would always have increased the prices speculatively at will at all points of time! Why would not they? When it gives them greater profits! It is precisely because of the fact that speculative manipulations of prices are not simply product of the subjective will or whims and fancies of capitalists. There are certain structurally-determined conditions under which speculative manipulations of prices of commodities is possible.

Fourth, why such conditions cannot prevail for long? Firstly, because any effective demand is effective demand at a particular price. If the prices increase, the effective demand decreases. If the effective demand decreases due to factors like overall decline in average incomes, then the prices too decrease. Therefore, increased effective demand is increased effective demand at a given price. Similarly, the high or low market-prices are such at a level of effective demand. Precisely, due to this circularity, Marx argues, the equations of supply and demand in and by themselves do not explain anything. If the short-term fluctuations in the market-price are explained by changing equation of supply and demand, the latter themselves are determined by social value and distribution of incomes, which again is determined by law of value.

Fifth, increased relative demand for any commodity also triggers some other processes. For instance, if the commodity in question cannot be supplied with domestic production and has to be imported, then the speculation in the prices of such commodities continues for comparatively longer periods of time and depends on international prices. However, if such commodity can be produced domestically, then increased demand and high market-prices lead to expansion of production of this commodity and therefore expansion in supply because capital flows towards the production of these commodities. Of course, there is time-lag in these developments to take effect. Nevertheless, eventually this happens. Once this happens, the very condition of speculative manipulations of prices is gone. Marx demonstrates this in the following passage:

This movement of capitals is always brought about in the first place by the state of market prices, which raise profits above the general average level in one place, and reduce it below the average in another. We are still leaving commercial capital out of consideration for the time being, as we have yet to introduce it, but as is shown by the paroxysms of speculation in certain favoured articles that suddenly break out, this can withdraw masses of capital from one line of business with extraordinary rapidity and fling them just as suddenly into another. (Marx, Capital, Volume 3)

That is the reason why speculative increase in prices of any commodity, including a wage-good, comes into existence only under specific conditions of supply and demand and that these conditions cannot be a long-term scenario because these conditions themselves trigger the movement of capital from one branch to another, eliminating the condition of under-supply. Marx argues that it is precisely the speculative rise in prices that destroys the conditions of the speculative rise:

This is about as logical as if he had said: The increased profit rate has been in consequence of a rise in commodity prices brought about by speculation, and to complain that the rise in prices destroys its own cause, i.e. speculation, is a logical absurdity, etc. Only for a usurer enamoured of his high rate of interest is it a logical absurdity that a thing can ultimately destroy its own cause. The greatness of the Romans was the cause of their conquests, and it was their conquests that destroyed their greatness. Wealth is the cause of luxury, and luxury has a destructive effect on wealth. The artful dodger ! There is no better sign of the idiocy of the present bourgeois world than the respect that the ‘ logic ‘of this millionaire, this ‘dung-hill aristocrat ‘, enjoyed throughout England. (Marx, Capital, Volume 3)

These are some general observations about the bouts of speculative rise in prices of commodities that apply to any and every phase of capitalism. The basic reason behind the above processes is nothing but the function of law of value.

These are among some of basic things that intellectual crooks like ‘The Truth’/’Yathaart’ brigade do not understand. They see speculative manipulations not as something which is regulated by the law of value itself, but as conspiracies of monopolies. Definitely, the cartels and joint-stock companies do engage in such activities, just like other factions of the capitalist class. However, they cannot conspire to bring about just any kind of manipulation of prices and cannot sustain such speculative prices for long, at will.

On the Question of Monopoly-Prices and Monopoly-Rent Once Again

The question of monopoly-price and that of monopoly-rent arising thereof, is totally different. These monopoly-prices can be sustained as long as the monopoly position of a capital is intact in any branch of production. As long as, a capital does not have any competitor in an industry or prevent other capitals from entering this industry, it can impose what Marx called an independent monopoly-price. The other kind of monopoly-price is the monopoly-price created by absolute ground-rent. However, in the case of independent monopoly-price, it is different. It is not the rent due to monopoly of landed property, as is the case of a determinate absolute ground-rent as a difference between the value of agricultural produce and the prices of production, which gives rise to monopoly-price. In the case of independent monopoly-price, it is this price itself that creates the monopoly-rent whereas in the case of monopoly-price created by a determinate absolute ground-rent, it is the ground-rent that exists due to monopoly of landed property and creates a monopoly-price. (See, Marx, Capital, Volume 3, Penguin Edition, p. 898, 906, and especially p. 910)

But then how is the quantification of this monopoly-price done? It is regulated by the effective demand for that particular commodity. If the monopoly-price is so high that the monopolist cannot sell even that amount of his commodities which can realize him a profit over and above average rate of profit, that is, a surplus-profit, he will decrease the monopoly-price. The sale of all units of his commodities is not his big concern, though monopolists generally sell their older unsold commodities too at lower prices later! Nor is this a concern for a monopolist that every consumer who wants his commodity gets it! For example, Apple sells old versions of i-phone at slightly slashed prices, once the new versions arrive. The main concern is to get that surplus-profit over and above average profit and that is why the available effective demand for that particular commodity does play a role in regulating the monopoly-price. That is why independent monopoly-price too is not unregulated; it is limited by the available effective demand, which itself is structured according to the distribution of incomes into wages, profit, interest and rent. Needless to say, that the latter is determined by law of value itself. (See Marx, Capital, Volume 3, Penguin Edition, p. 910). This is something that ‘The Truth’/’Yathaarth’ brigade of buffoons do not understand. One of their authors Ajay Sinha has come up with a novel theory that monopolies do not get surplus-profit (regulated by law of value) but get “maximum profit” (unregulated by anything!).

Such an argument is tantamount to abandoning the law of value itself. It fails to understand two things: first, all kinds of monopoly-rents are regulated in one way or another by law of value; second, only that much of value can be realized as is produced. Therefore, any kind of monopoly-rent can only change the distribution of surplus-value, but not the total magnitude of value itself. (See, Marx, Capital, Volume 3, Penguin Edition. p. 1001).

That is why, such theory of “maximum profits” exacted by monopolies is absurd and nonsense and has nothing whatsoever to do with Marx. The funny thing that happened with “Truthseekers” was that since some textbooks and writings of great teachers, too, have used the term “maximum profit” as a synonym of surplus-profit, consequently, our kulak-loving imbeciles got confused! They thought, obviously without reading the entire section or investigate the matter at hand, that the evil monopolies must be realizing an unregulated, arbitrary “maximum profits” which is something even more despicable than Marx’s “surplus-profit” and it was something that Ajay Sinha and “Truthseekers” have discovered for the first time as Marx and Lenin were not aware about this “maximum profit” of corporates! This is a classical example of how the minds of dimwits function!

Conclusion

These are some general observations on the question of historical prices of food items, the reason for their movement, the nature of speculative manipulations in the prices of commodities and the conditions under which such speculative rise in prices come into and go out of existence, the nature of monopoly-price and monopoly-rent, the character of the loot and plunder of simple commodity producers by capital on the one hand and the co-sharing of surplus-value between two capitalists as entrepreneurial profit and commercial profit, etc. These are issues that are being ridiculously confused by certain imbeciles, some of which are gathered around ‘The Truth’/’Yathaarth’ magazine. The latter are particularly relentless in propagation of idiocy and inanity among the unsuspecting but promising young students of Marxism.

However, some of these questions have also been misunderstood by a lot of serious and promising students of Marxism as well as many Marxist academicians. There has been a persistent tendency within the communist movement as well to oppose the big monopoly capital without putting the entire capitalist system and entire capitalist class in the dock, at least since the Second World War. This understanding of monopoly capitalism has serious problems as it promotes class alliance between other factions of bourgeoisie against the big monopoly capital. The dangers associated with such an approach can easily be comprehended by any revolutionary communist. The present Narodist and economic romanticists who are stirred into action whenever big capital threatens the small capital, be it through FDI in retail or through farm laws fail to understand that the working class opposes monopoly capital as well as the capitalist class from its own independent class position. In no way can it capitulate to small capitalist class, or become a palanquin-bearer for them, or strive to save them in any way. The working class will fight for its class allies, namely, the poor peasants and semi-proletariat and lower-middle class, will make sacrifices of its own particular immediate economic interests, whenever needed for the revolutionary strategic class alliance, otherwise it would be committing the mistake of workerism, a kind of identity politics within the working class where ‘workers’ do not represent a political class but an identity. However, in the name of ‘thinking politically’ certain comrades are making the opposite mistake of class collaboration with and capitulation to the rich farmers and kulaks who are the principal exploiters and oppressors of the working class in general and agricultural workers, poor peasants and dalit working masses, in particular. Politically speaking, it is a fatal mistake as it sacrifices the independent class political position of the proletariat and makes it a flunkey of small capital.

These are some essential things to understand if we aim to make even one step forward in the movement of the working class and the revolutionary process in general.